| Home |

___ History of Cuba |

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND |

|

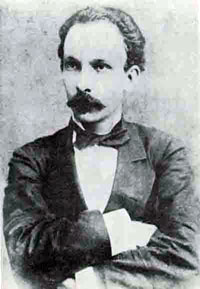

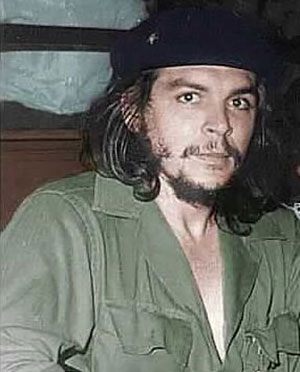

Cristóbal Colón (Christopher Columbus) claims the New World. On 27 October 1492 Columbus sighted Cuba, he named the island Juana.  José Martí José Martí (28 January 1853–19 May 1895) Cuban independence leader and national hero. Through his writings and political activity, he became a symbol for Cuba's bid for independence against Spain in the 19th century. The Independence Struggle and Beginning of U.S. Hegemony: Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Cuban loyalty began to change as a result of Creole rivalry with Spaniards for the governing of the island, increased Spanish despotism and taxation, and the growth of Cuban nationalism. These developments combined to produce a prolonged and bloody war, the Ten Years’ War against Spain (1868–78), but it failed to win independence for Cuba. At the outset of the second independence war (1895–98), Cuban independence leader José Martí was killed. As a result of increasingly strained relations between Spain and the United States, the Americans entered the conflict in 1898. Already concerned about its economic interests on the island and its strategic interest in a future Panama Canal, the United States was aroused by an alarmist “yellow” press after the USS Maine sank in Havana Harbor on February 15 as the result of an explosion of undetermined origin. In December 1898, with the Treaty of Paris, the United States emerged as the victorious power in the Spanish-American War, thereby ensuring the expulsion of Spain and U.S. tutelage over Cuban affairs. On May 20, 1902, after almost five years of U.S. military occupation, Cuba launched into nationhood with fewer problems than most Latin American nations. Prosperity increased during the early years. Militarism seemed curtailed. Social tensions were not profound. Yet corruption, violence, and political irresponsibility grew. Invoking the 1901 Platt Amendment, which was named after Senator Orville H. Platt and stipulated the right of the United States to intervene in Cuba’s internal affairs and to lease an area for a naval base in Cuba, the United States intervened militarily in Cuba in 1906–9, 1917, and 1921. U.S. economic involvement also weakened the growth of Cuba as a nation and made the island more dependent on its northern neighbor.  U.S.-backed Dictator Fulgencio Batista, leader of Cuba from 1933-1944, and from 1952-1959, before being overthrown as a result of the Cuban Revolution. U.S.-backed Dictator Fulgencio Batista, leader of Cuba from 1933-1944, and from 1952-1959, before being overthrown as a result of the Cuban Revolution.The end of the early Batista era during World War II was followed by an era of democratic government, respect for human rights, and accelerated prosperity under the inheritors of the 1933 revolution—Grau San Martín (president, 1944–48) and Carlos Prío Socarrás (president, 1948–52). Yet political violence and corruption increased. Many saw these administrations of the Cuban Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario Cubano—PRC), more commonly known as the Authentic Party (Partido Auténtico), as having failed to live up to the ideals of the revolution. Others still supported the Auténticos and hoped for new leadership that could correct the vices of the past. A few conspired to take power by force.  Fidel Castro on his way to bring down the Batista regime.  Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14 June 1928 – 9 October 1967) a key figure of the Cuban Revolution in its struggle against monopoly capitalism, neo-colonialism, and imperialism. Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14 June 1928 – 9 October 1967) a key figure of the Cuban Revolution in its struggle against monopoly capitalism, neo-colonialism, and imperialism.Che was executed on 9 October 1967 (aged 39) at the instigation of René Barrientos, then President of Bolivia who came to power in the aftermath of the overthrow of the government of Paz Estenssoro in a United States of America's CIA-backed coup. Cuba’s alliance with the Soviets provided a protective umbrella that propelled Castro onto the international scene. Cuba’s support of anti-U.S. guerrilla and terrorist groups in Latin America and other countries of the developing world, military intervention in Africa, and unrestricted Soviet weapons deliveries to Cuba suddenly made Castro an important international contender. Cuba’s role in bringing to power a Marxist regime in Angola in 1975 and in supporting the Sandinista overthrow of the dictatorship of Nicaragua’s Anastasio Somoza Debayle in July 1979 perhaps stand out as Castro’s most significant accomplishments in foreign policy. In the 1980s, the U.S. military expulsion of the Cubans from Grenada, the electoral defeat of the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, and the peace accords in El Salvador and Central America showed the limits of Cuba’s influence and “internationalism” (Cuban missions to support governments or insurgencies in the developing world). A Continuing Cuban-U.S. Cold War: The collapse of communism in the early 1990s had a profound effect on Cuba. Soviet economic subsidies to Cuba ended as of January 1, 1991. Without Soviet support, Cuba was submerged in a major economic crisis. The gross national product contracted by as much as one-half between 1989 and 1993, exports fell by 79 percent and imports by 75 percent, the budget deficit tripled, and the standard of living of the population declined sharply. The Cuban government refers to the economic crisis of the 1990s and the austerity measures put in place to try to overcome it euphemistically as the “special period in peacetime.” Minor adjustments, such as more liberalized foreign investment laws and the opening of private (but highly regulated) small businesses and agricultural stands, were introduced. Yet the regime continued to cling to an outdated Marxist and caudillista (dictatorial) system, refusing to open the political process or the economy. The traditional Cold War hostility between Cuba and the United States continued unabated during the 1990s, and illegal Cuban immigration to the United States and human rights violations in Cuba remained sensitive issues. As the post-Soviet Cuban economy imploded for lack of once-generous Soviet subsidies, illegal emigration became a growing problem. The 1994 balsero crisis (named after the makeshift rafts or other unseaworthy vessels used by thousands of Cubans) constituted the most significant wave of Cuban illegal emigrants since the Mariel Boatlift of 1980, when 125,000 left the island. A Cuban-U.S. agreement to limit illegal emigration had the unintended effect of making alien smuggling of Cubans into the United States a major business. In 1996 the U.S. Congress passed the so-called Helms–Burton law, introducing tougher rules for U.S. dealings with Cuba and deepening economic sanctions. The most controversial part of this law, which led to international condemnation of U.S. policy toward Cuba, involved sanctions against third-party nations, corporations, or individuals that trade with Cuba. The U.S. stance toward Cuba became progressively more hard-line, as demonstrated by the appointment of several prominent Cuban-Americans to the administration of George W. Bush. Nevertheless, as a result of pressure from European countries, particularly Spain, the Bush administration continued the Clinton administration’s policy of suspending a provision in the Helms–Burton Act that would allow U.S. citizens and companies to sue foreign firms using property confiscated from them in Cuba during the 1959 Revolution. Instead, the Bush administration sought to increase pressure on the Castro regime through increased support for domestic dissidents and new efforts to broadcast pro-U.S. messages to Cubans and to bypass Cuba’s jamming of U.S. television and radio broadcasts to Cuba.  Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (born 13 August 1926) was until July 2006 Cuba's President of the Council of state, Commander in Chief of the armed forces, President of the Council of Ministers, and First Secretary of the Cuban Communist Party. Internal Political Developments: A crack opened in the Cuban system in May 2002, when a petition with 11,000 signatures—part of an unusual dissident initiative known as the Varela Project—was submitted to the National Assembly of Popular Power (hereafter, National Assembly). Started by Oswaldo José Payá Sadinas, now Cuba’s most prominent dissident leader, the Varela Project called for a referendum on basic civil and political liberties and a new electoral law. In the following month, however, the government responded by initiating a drive to mobilize popular support for an amendment to the constitution, subsequently adopted unanimously by the National Assembly, declaring the socialist system to be “untouchable,” permanent, and “irrevocable.” In recent years, Cuban politics have been dominated by a government campaign targeting negative characteristics of the socialist system, such as “indiscipline” (for example, theft of public and private property, absenteeism, and delinquency), corruption, and negligence. Under the campaign, unspecified indiscipline-related charges were brought against a member of the Cuban Communist Party and its Political Bureau, resulting in his dismissal from these positions in April 2006. One of the world’s last unyielding communist bulwarks, Castro, hospitalized by an illness, transferred power provisionally to his brother, General Raúl Castro Ruz, first vice president of the Council of State and Council of Ministers and minister of the Revolutionary Armed Forces on July 31, 2006. Fidel Castro’s unprecedented transfer of power and his prolonged recovery appeared to augur the end of the Castro era. History Text Source: Library of Congress |

|

One World - Nations Online .:. let's care for this planet Promote that every nation assumes responsibility for our world. Nations Online Project is made to improve cross-cultural understanding and global awareness. More signal - less NOISE |

| Site Map

| Information Sources | Disclaimer | Copyright © 1998-2023 :: nationsonline.org |